So what could a K-12 STEM school look like, if one were devoted to maximizing love, mastery, and purpose — and could draw upon the weapons of Imaginative Education?

Below is what Kristin and I wrote up when asked this question. Advanced warning: there are some pretty exciting things in here.

SCIENCE / TECHNOLOGY / ENGINEERING

1. HAVE CHILDREN ENGAGE WITH REAL (PHYSICAL) THINGS.

- Bring in plants to the classroom, and animals, and mechanical objects. Bring in food, too, and cook it together daily.

- This means having hermit crabs, birds, and fish in the classroom. It also means bringing in incandescent lightbulbs, vacuum cleaners, paint, old telephones & microphones, pumps, and small gasoline engines.

- Some of these would stay in the classroom long-term; others could migrate from classroom to classroom at regular intervals. (The mechanical objects, for example, would move every two weeks.)

- Also, get the kids out of the classroom — repeatedly visit a specific site to get a sense of how the various elements of an ecosystem work together.

- The class’s goal is to understand these objects as well as possible.

- Kids would poke, prod, and take apart these things. They’d feed them, nurture them, and clean up after them. They might even shake, sniff, and lick them! Bring in as many senses as possible.

- These would get kids into physics, chemistry, biology, geology, and ecology. (At present, we're struggling to incorporate astronomy into this. If you’ve any thoughts, we’d love to hear them!)

2. TRAIN CHILDREN IN SPECIAL TOOLS FOR OBSERVATION.

- Ordinary physical engagement isn’t enough — kids need to develop specialized techniques that will help them notice in more detail.

- One of these techniques is a game of just listing out everything they notice. (We’ve adapted this from a famous story told of the scientist Louis Agassiz, which is well worth reading.) It’s incredible how doing this pushes us far beyond our initial interpretation of things, which we had foolishly assumed to be more-or-less all there was to see.

- Another of these techniques is to teach children to draw realistically: drawing being a way to externalize observation (and to make obvious what we’re not seeing). There are a few outfits in Seattle that do this, and some DVDs and books that teach it as well.

- Another of these is to use physical tools — especially magnifying glasses and microscopes — to uncover worlds we’d otherwise not have access to. (The secret is to provide these things as tools for students to use to explore objects they’ve chosen, rather than assigning the objects.)

3. PROMPT STUDENTS TO DO THEIR OWN RESEARCH.

- Fill the classroom with engaging popular books of science — both for children and for adults.

- Allow kids to have a limited number of web searches per day. (This creates scarcity and value, and forces students to be more discerning in their browsing.)

- Prompt kids to ask parents and community members what they know about these topics.

4. DEVELOP A CULTURE OF PONDERING TOGETHER.

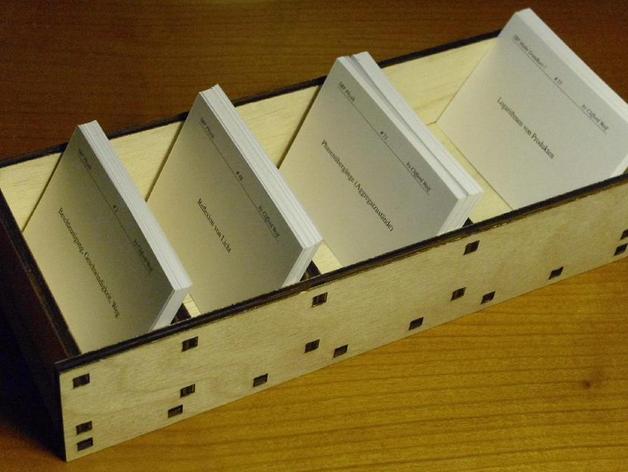

- Give kids blank books (“commonplace books”) in which to make their observations, draw pictures, and pose questions.

- Once each week, students submit one question they’d most like to get the class’s help pondering (e.g. “Why doesn’t the filament burn up?”). These questions get written onto the chalkboard wall.

- Each day, time is set aside for offering up possible answers to those questions — along with new sub-questions that the original question spawns. Those are also written down on the board, which becomes a giant thought map.

- Have students ask parents and community members what they think the answers to these specific questions might be.

- The immediate job of the teacher isn’t to answer these questions directly, but rather to facilitate thinking well — challenging the kids’ theories, and praising effort. (This is Socratic dialogue, and though I think I can teach it in person, I’d need to look into how to teach it remotely. There are some good books on this, published by people associated with the Philosophy for Children movement, which has a center in Seattle.)

5. STEER THEM TOWARD FULLER UNDERSTANDING.

- The longer-term job of the teacher is to steer children toward the correct answer. To do that, the teacher needs to, of course, herself understand the scientific phenomenon deeply. To help relatively untrained teachers do this, we could put together informational materials — scans of relevant books, PDFs of relevant webpages, and YouTube video explanations, for example. We’d also want to make it easy for teachers to ask each other questions — teachers, in a way, take on the role that the students are doing. We’d perhaps also want to pay some scientists (or PhD students) to directly answer questions online, and preserve those answers for future teachers.

- And we can go beyond just providing information for teachers — we can help pre-prepare lesson plans on the Imaginative Education framework. The goal here is to show students how this physical phenomena is really, really interesting — in addition to showing how it works. (Some students are born with a love for scientific phenomena — for the rest of it, it needs to be cultivated. This starts with the teacher falling a little in love with the topic.) I’d be thrilled to put you guys in touch with some of the leading science-teaching experts in the Imaginative Education community.

6. HAVE THEM TEACH OTHERS.

- At the end of the project, students demonstrate their understanding by making something that teaches the science to others.

- Most frequently, this should be a written report, which we can use to hone writing abilities. These would be authentic projects, written for specific audiences — parents, and perhaps younger students.

- These demonstrations can also be done in other media: students can draw diagrams, shoot photos, make movies, write songs, and draw comics to explain the science.

7. TELL THE STORIES BEHIND KNOWLEDGE.

- Tell the stories of the things we’re studying: the stories of the scientific and mathematical insights, and of the technological breakthroughs.

- Focus particularly on wrong ideas and inventions that didn’t work (for example, aether, classical elemental theory, phlogiston, and abiogenesis — or one of the planes before the Wright Brothers, one of the lightbulbs before Edison). We need to make this kind of “failure” okay. We also want to appreciate how clever the correct ideas really are!

- We can tell those stories alongside the objects we’re studying, and tell them as part of the Big Spiral History framework (14 billion years in 4 years, encountered not once, not twice, but thrice!).

- Use these stories as “think-alongs”: as excuses to help kids do their own thinking. We can tell the stories slowly, asking kids to interpret the evidence that e.g. Newton is observing, and seeing if we can figure out how Newton made the intuitive leaps that he did.

- Start with the Big Bang, and quickly give the whole narrative of the universe. This gives us a foundation to tell the stories of where all material things (grass, dirt, rocks, carbon atoms, nuclei…) came from in the first place.

Stay tuned t'morrow for the math component of our plans — as well as what all of this leaves out!

The thing is, this is actually true — for all genders.

The thing is, this is actually true — for all genders.

Luke Epplin at theatlantic.com

Luke Epplin at theatlantic.com