I've been musing on this "a new kind of school" idea for a few years now, but I may have grasped the larger purpose of the idea just this week. (Finally!) It's this:

The job of schooling is to be a bridge between human nature and the needs of the future. School's purpose is to construct the traits we need out of the traits we're born with. The classroom turns our inherited attributes into the attributes we want.

To the extent to which this idea is right, it should seem obvious. Also, it should not only be true for our school, but for any school, past or present.

It might, in short, seem unhelpfully broad! But I've found it powerful, because it calls our attention to three separate concepts: human nature, the needs of the future, and the link between them.

Better yet, it suggests three fundamental tasks that anyone who seeks to create a new kind of schooling needs to accomplish.

The 22nd century?

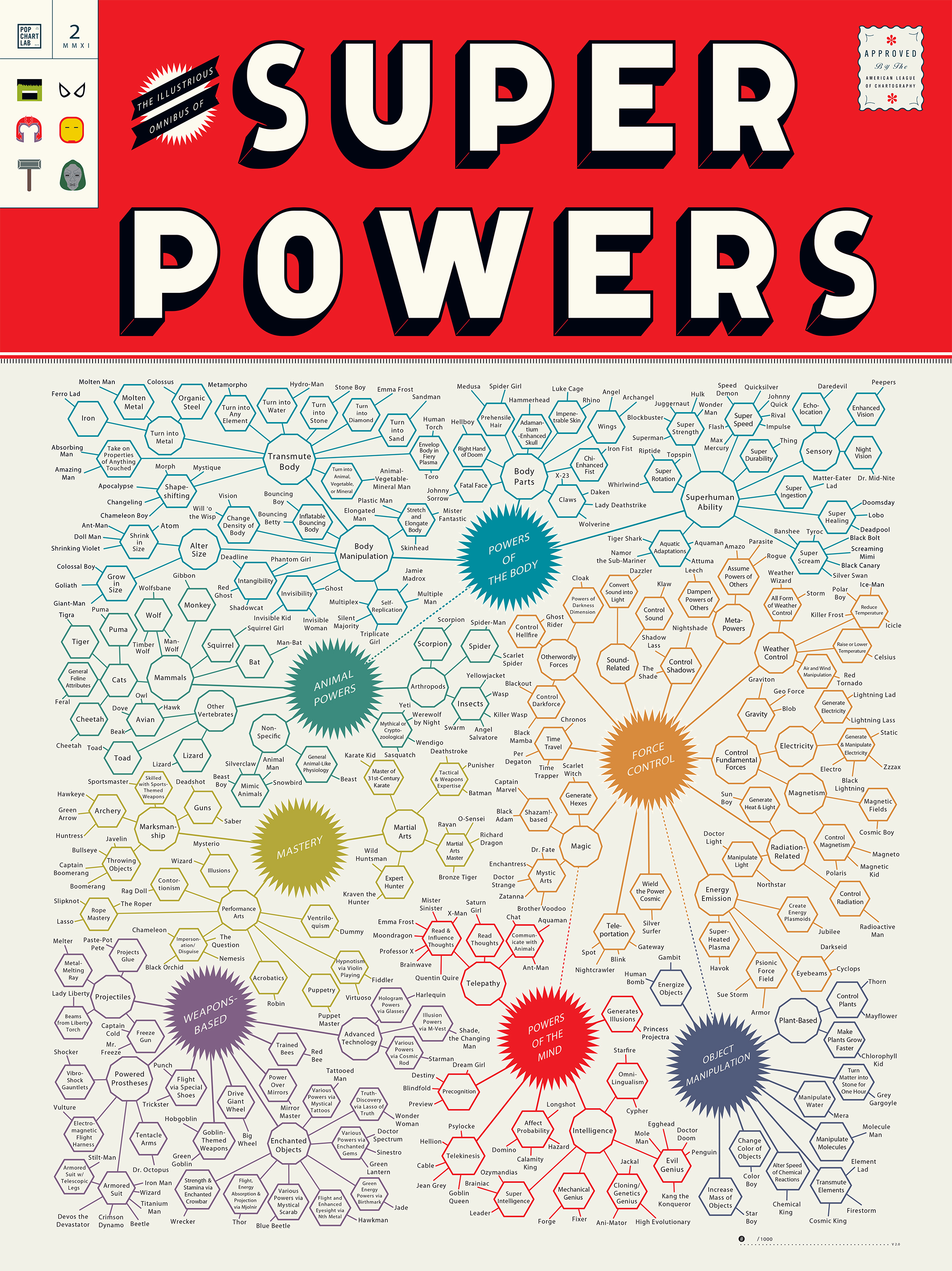

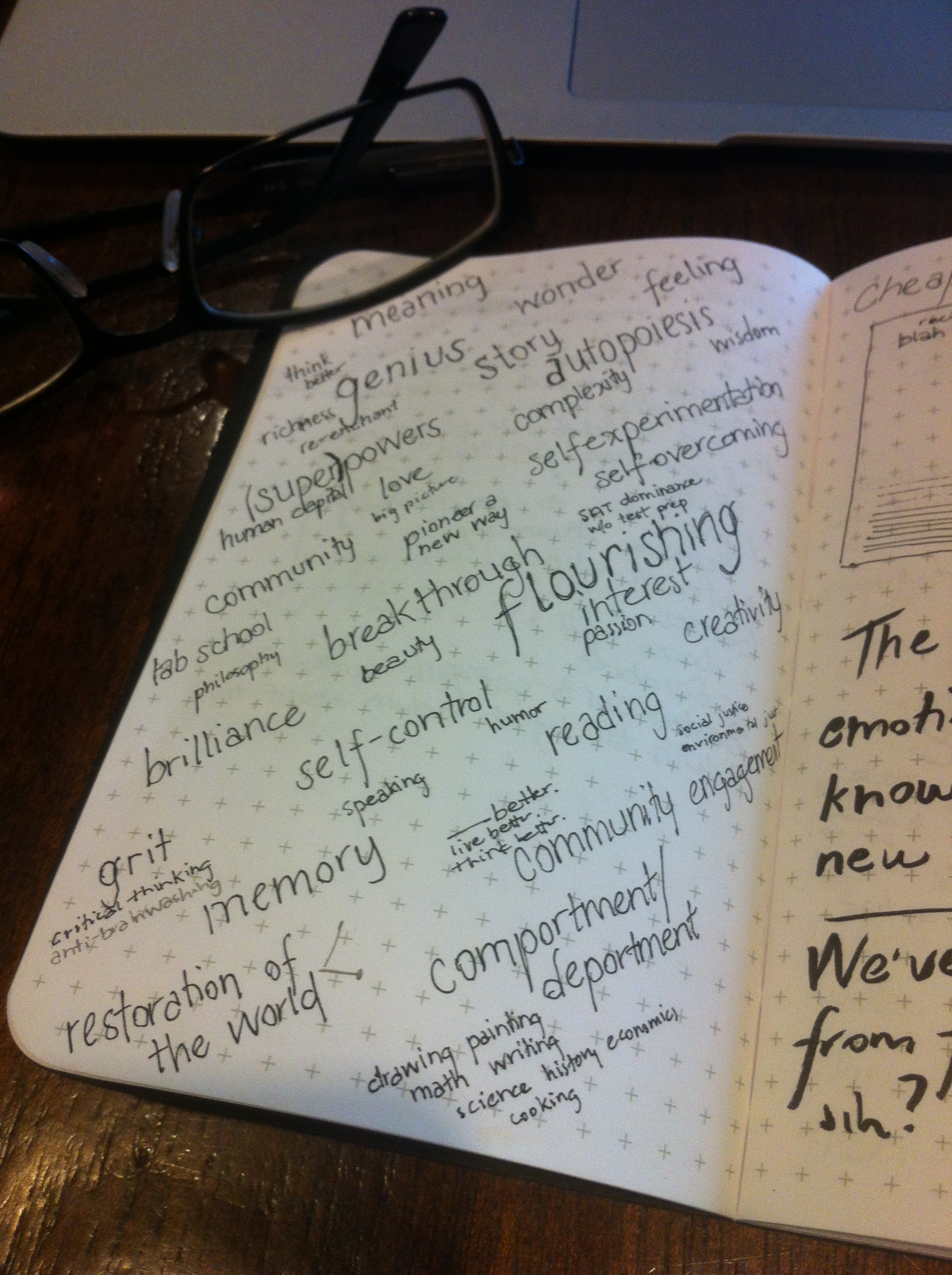

1. We need to decide, explicitly, what kinds of goals we want our students to attain. Do we want them to exhibit stupendous creativity? Be brilliant at understanding themselves? Be able to think like economists? mathematicians? political theorists? mechanics? ecosystems biologists? Write lucidly, and reason rationally? Do we want them to give a damn? Have empathetic understandings of other cultures? Have gumption? Understand their own cognitive biases? Not fall prey to the host of cognitive biases human minds are prone to?

This requires philosophical reflection; it also (necessarily) requires future forecasting. What do we think the world will be like in twenty, and thirty, and eighty years? What skills and habits and dispositions will benefit society then?

Obviously, we've still got a ways to go before 2099 CE comes around. But I'm finding it useful to think about the job of "reinventing schooling for the 22nd century!" Maybe that's just because I'm so tired of hearing about "21st century skills." But it's also that I find it thrilling to go so big picture. And it's also because I find it humbling to recognize that, even if our schools take off as successfully as I dream, they'll still take a century to spread widely.

But most of all, it's a helpful reminder that the effects we have on our students will last a long time. A kid who's five now stands a reasonably good chance of peeking into the 22nd century. The students who join our school in its early years will (according to actuarial tables!) be almost certain to make it there.

What kind of society do we want to live in? In making a school, we're making the future — or at least implicitly trying to. Imagining our school as "a bridge to the 22nd century!" puts that on center stage.

Human nature: no, really.

But it's not enough to have goals!

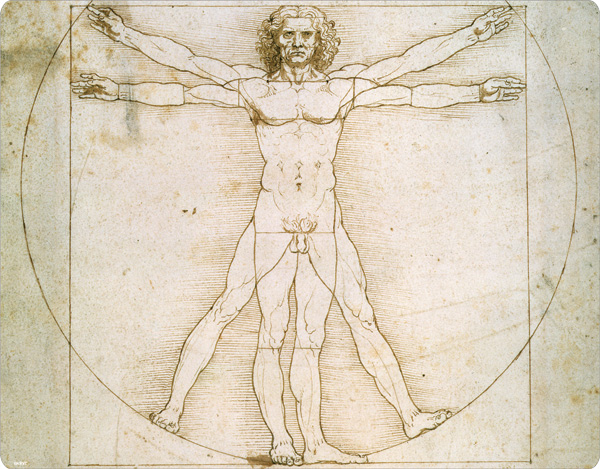

2. We need to observe, with clear eyes, what traits our species comes pre-equipped with. What are we really good at? What are our limitations? What are our deep motivations? What are our cognitive oddities?

Human nature isn't simple. It's a klugey muddle, dependent on our quirky evolutionary history. Do we seek meaning? Status? Achievement? What are the things that limit us — our attention, our memory, our interests? Do we have a hard time connecting with more than 150 people? Are there aspects of our nature that we want to curtail — tribalism, self-aggrandizement? Are we natural-born procrastinators? Do we need exercise?

A good deal of educational thinking isn't grounded in a realistic appraisal of human nature. This is even true of some of the best educational thinking. The brilliant Kieran Egan, for example — and I hope he reads this, if only so my praise embarrasses him! — writes:

human beings don't have a nature. Well, that overstates it to underline a point. There are obviously regularities in human mental development, but they are so tied up with our social experience, our culture, and the kinds of intellectual tools we pick up that we can't tell whether the regularities are due to our nature, to our society, to our culture, to our intellectual tools, or what. (The Future of Education, p. 26)

This used to be the common wisdom. It's not anymore — the blooming of the sciences of human nature is one of the most exciting intellectual movements of our age. Jonathan Haidt exults:

nowadays cross-disciplinary work is flourishing, spreading out from the middle level (psychology) along bridges (or perhaps ladders) down to the physical level (for example, the field of cognitive neuroscience) and up to the sociocultural level (for example, cultural psychology). The sciences are linking up, generating cross-level coherence, and, like magic, big new ideas are beginning to emerge. (The Happiness Hypothesis, p. 227)

This new understanding is generating wonderful fruit: from how to reduce violence, to how to eat, to how to combat depression. And so many more things beside.

We can do the same with education. Our job, then, is to bring the question of school into the conversation about human nature.

School is the bridge — or, many bridges.

Once we have a vision of what we want to get, and have an understanding of what millions of years of evolution have already given us, our task is surprisingly simple:

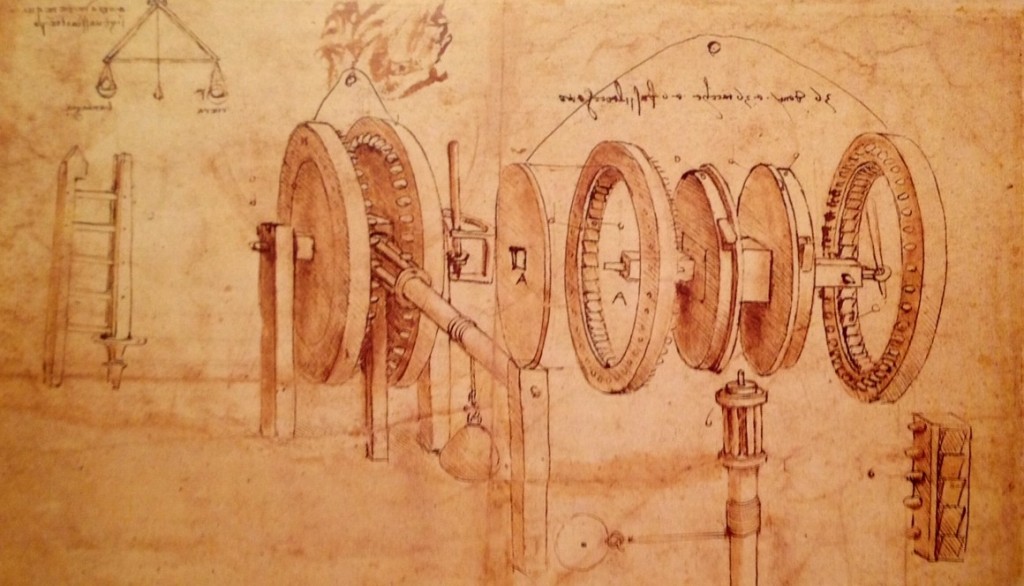

3. We need to find tools that help extend the traits of human nature to our goals. The beautiful thing is that many of these tools already exist: they've been in use in a diversity of schools for decades and centuries! And there's no reason we have to limit ourselves to tools created for schools, in particular — education is a grander task.

I'm writing "tools": what I mean is curriculum, practices, technology, theories, and frameworks. I mean harebrained notions. I mean tried-and-true best practices. We need to be as inclusive in our search as we can: we can survey all of human culture, and consider the tools that seem to have worked.

This step is some of what I've been doing on this blog already. We can consider Imaginative Education and JUMP Math, Anki and meditation. We can consider Socratic seminars, poetry memorization, and adventure playgrounds. We can consider art appreciation, play planning, and gamification. We can consider guided social entrepreneurship, Big History, and realistic drawing. We can consider dancing and singing.

We don't need to reinvent the wheel. We can recreate the best things that anyone has done in education, and bring them all into one place.

And this needn't be a mishmash of competing practices, because we have a framework: the human nature they already have, and the goals we want our students to attain. We just need to figure out what tools will best help them get from the one to the other.

I'll end this meditation here, and promise to pick up the topic again on Monday. There are some crucial aspects to this I haven't mentioned — who's already doing this, who's not doing this, who hates this, and who might love this.

I'll also suggest some unexpected advantages that might come from making this our big framework as to what goes into our new kind of school!

One thing I haven't done a good job of, though, is giving any sign that I recognize how controversial a lot of this is. Oh, I do — and maybe love the framework even more for that! (A personal failing, I'll agree!)

Please do feel free to criticize (kindly, of course) in the comment boxes — in so doing, you'll be helping out our future school!

Our trinity of goals for our school begins with love and progresses, in middle school, to mastery. Our third goal — reaching its apex in the high school curriculum, but present at all grades — is wisdom.

Our trinity of goals for our school begins with love and progresses, in middle school, to mastery. Our third goal — reaching its apex in the high school curriculum, but present at all grades — is wisdom.

Ours can be a school of mastery.

Ours can be a school of mastery. And we're back!

And we're back! Luke Epplin at theatlantic.com

Luke Epplin at theatlantic.com  Nietzsche wrote:

Nietzsche wrote: