There's a debate — a stupid one! — about what should be on the walls of a classroom. If you'll permit me to simplify for the sake of mockery:

Side #1: Crap! Trash! Smother the walls with garbage! Garish colors! COMIC SANS!

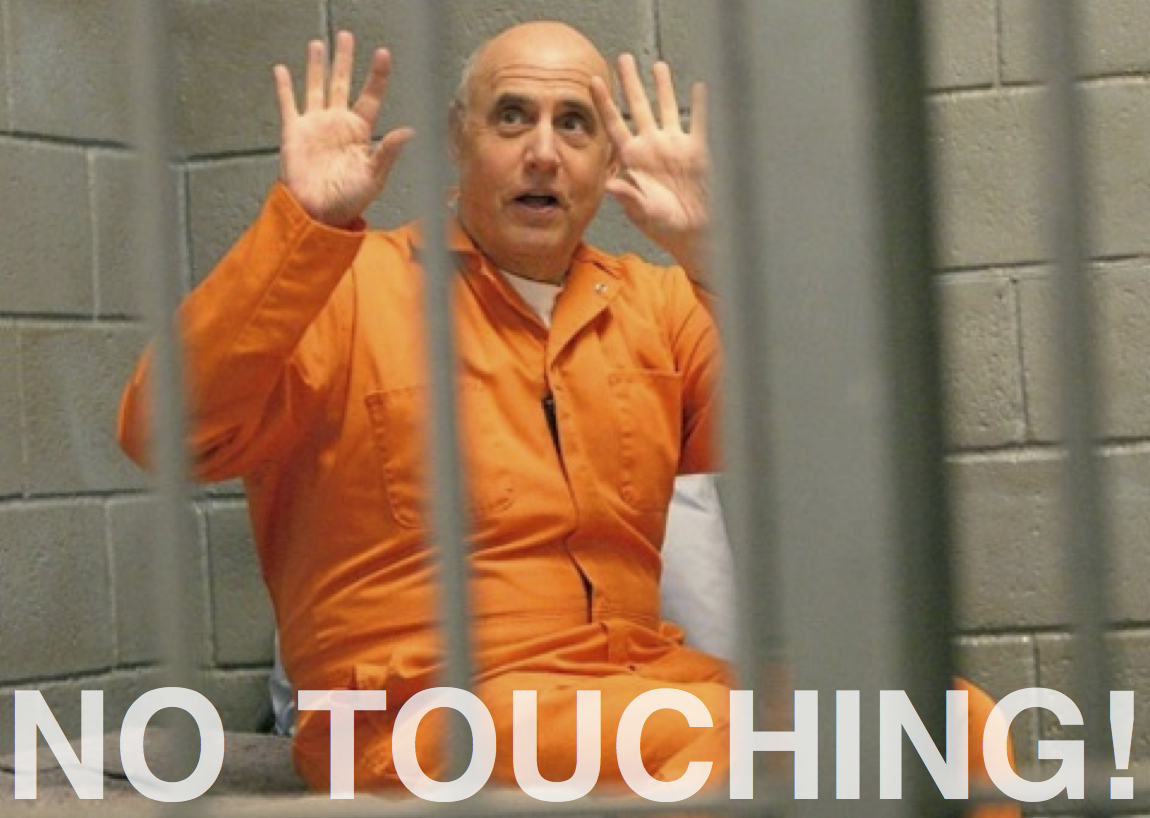

Side #2: Sparse! Austere! Think monastic cells! Think SUPERMAX chic!

This is over-simplification, but as educational über-psychologist Daniel Willingham points out, some actual research on the effects of classroom decoration is stuck on stupid (my words, not his). A recent study compared more-or-less the above extremes. (Supermax chic won.)

Sigh. Maybe someday our society will actually have some useful debates on educational matters. For now, we'll just shake our heads (and the dust off our feet) and strike out in a sensible direction.

Built environment matters.

As Churchill told the House of Commons in 1943, addressing the rebuilding of the debate chamber which had been destroyed by German bombs two years earlier:

We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us.

What our school physically looks like matters, because it will affect how we feel, and how we think.

Today: feeling.

Feeling, & Beauty

Beauty matters. Aesthetics make us feel by tapping into the most primal modules of our psychology. A sense of beauty isn't some recent cultural add-on — it's deeply evolved into our minds. It's something we share with other animals.

As Steven Pinker writes, in How the Mind Works:

The expression "a fish out of water" reminds us that every animal is adapted to a habitat. Humans are no exception. We tend to think that animals just go where they belong, like heat-seeking missiles, but the animals must experience these drives as emotions not unlike ours. Some places are inviting, calming, or beautiful; others are depressing or scary. The topic in biology called "habitat selection" is, in the case of Homo sapiens, the same as the topic in geography and architecture called "environmental aesthetics": what kinds of places we enjoy being in.

A feeling of beauty is evolution's carrot to get us to move toward a certain place. A feeling of ugliness is evolution's stick to get us out of a place.

Beauty pulls us; ugliness pushes us. Aesthetics move us. It was true on the savannah, and it's true today.

Pinker again:

Environmental aesthetics is a major factor in our lives. Mood depends on surroundings: think of being in a bus terminal waiting room or a lakeside cottage.

Ugly classrooms are bus terminals; beautiful classrooms are lakeside cottages. Beauty can be Zoloft.

For all the romantic things we can say about our school — a place of love! and wonder! and flourishing! — it will, by necessity, also sometimes be a place of discomfort. We need all the mood-enhancers we can get.

But what do we mean by "beauty"? In what ways should our classes be beautiful? I'll explore the specifics in later posts, but today I'll suggest two attributes: we should seek to make our classrooms calming, and interesting.

Calming

The Reggio Emilia people are really onto something:

And, come to think of it, so are the Montessori people:

And those Waldorf people? Nailed it!

Compare any of those to this photo of a more typical classroom:

Not especially heinous — I found much more egregious photos online! — but (for our purposes) "helpfully unbeautiful". We've got harsh florescent lights, white walls, cheap surfaces and floors, and stuff (pedagogical stuff) cluttering the walls.

This is not a place that makes it easy to fall in love.

This is, if anything, a place that makes it easy to fall in hate.

Or maybe that's too strong — maybe I react to aesthetics more strongly than do most people. (Well: I do.) At the very least this isn't a place that invites a student to feel safe and comfortable and cared for.

Some points for us to take:

Our school won't have harsh, florescent lights, uniformly white walls, cheap surfaces, linoleum floors, or stuff cluttering the walls.

We'll attempt, instead, to achieve some degree of serenity. We'll be riling the kids up with everything we teach them — it'll be nice to have a calm, restful baseline to bring them down to between lessons.

Interesting

Calm doesn't mean boring: our classrooms (and the other rooms in our school) will be filled with things that are worthy of students' attention during their free time. (Again, we'll be starting the early grades with a Montessori-esque model: there will be large swaths of the day when students will choose among various educational activities to do themselves.)

Again, the Reggio Emilia schools do this quite well —

Note the mirror-tripod, the aloe plant, the photos on the back wall.

The Montessori people excel at making interesting classrooms —

Note the books, the plants, and the planets. And the easel. And the playsets!

And it's not unheard of for Waldorf classrooms to have tree houses. Tree houses!

We can borrow from all of these — and many more beside.

We have to: making a school for humans means making classrooms that fit our deeply evolved needs.

Coming soon — classrooms that help us think better.

Luke Epplin at theatlantic.com

Luke Epplin at theatlantic.com